Family Conflict and Management

Conflict within families is normal, and, with help, it can be managed. While the nature of conflict can change between generations - screen time, for example - the sources of the conflict remain the same, chiefly, changes in the developing teenage brain. This sections explores practical measures parents and carers can take to restore calm to the family home.

.png)

Family Conflict and Management

After completing this section, you will be able to: understand how screen time can strain family relationships; ways to talk during conflict that won’t make the situation worse; and how parenting strategies like family meetings and behaviour contracts can help.

- Screen Time

- Resolving Conflict

- Specific Parenting Strategies

Screen Time

A common cause of family conflict is screen time.

'Screen time' refers to how long a person spends using devices with screens, such as smartphones, tablets, computers, televisions, and gaming consoles.

There are three types of screen time:

Digital Agreement

For parents and carers who need to limi their young person's time online, a digital family agreement can help.

A digital family agreement is most effective when it is developed collaboratively, rather than being strictly imposed. This helps teenagers understand the reasoning behind the rules and encourages them to take ownership of their digital habits.

If a digital family agreement doesn’t work, parents can take a more hand-on approach via parental controls, which can be used to manage screen time, block content, prevent purchases and prevent strangers from contacting your young person. Research shows that parental controls are most effective in supporting digital wellbeing when combined with open and regular discussions about online activities.

For a more in-depth look at the issue of screen time, as well as other issues related to young people and feeling safe online, we recommend visiting the Internet Matters website.

A digital family agreement typically includes:

1. Screen Time Limits

Set a daily or weekly limit on passive screen time to ensure a healthy balance between online and offline activities.

2. Device Free Zones & Times

Establishing tech-free areas (e.g., bedrooms) and times (e.g., during meals or before bedtime) to promote family bonding and proper sleep.

3. Education vs Entertainment

Differentiating between passive screen time and active screen time, ensuring online time related to education comes first.

4. Tracking

Determine if and how you will track device usage, social media activity, and online interactions.

5. Online Safety Rules

Teach responsible internet use, privacy protection, and respectful communication to prevent cyberbullying or risk-taking.

6. Rule Breaking

See if you can get your young person to agree to reasonable consequences if rules are broken, such as reducing the amount of screen time further than already agreed.

Resolving Conflict

I-Statements

As well as listening to understand other’s needs and emotions, it’s also important that we can express our own needs and emotions clearly.

Before attempting to resolve a conflict, take time to think about what you need and what you are feeling. Try using the Feelings Wheel or the Emotion Iceberg to explore your feelings. Then think about what your needs are – are you willing to compromise?

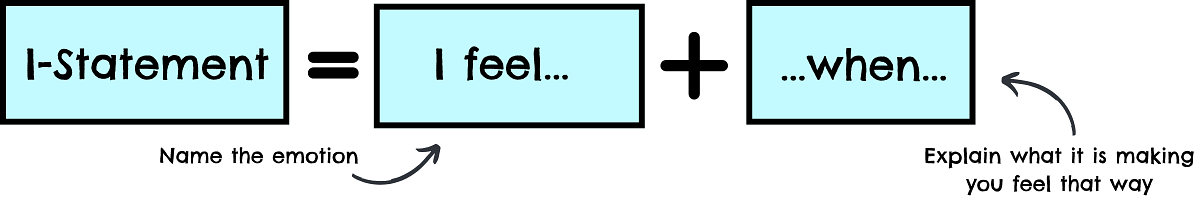

Often when we are in conflict situations, we use blaming statements such as ‘you always’ or ‘you never’. These statements don’t leave space to explain how we are feeling and can often cause the other person to become defensive. If we use ‘I’ and ‘we’ instead, we can clearly express our needs and encourage others to do the same. These are called ‘I-Statements’ and are made up of two parts:

Parental Emotional Regulation

Emotional Regulation - The Basics

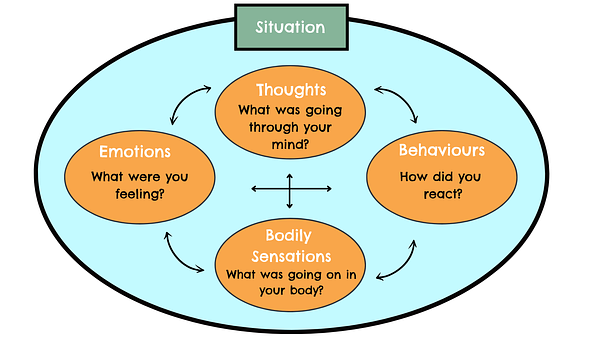

Emotional regulation is important because our emotions drive how we behave and feel. If we can soothe feelings of anger, we can learn to approach conflict with calm.

It’s especially important for parents because it directly affects their ability to respond to their children in a calm and supportive way.

Some things to think about:

- If parents and carers can regulate their emotions during arguments, they are in a good place to make decisions that will bring the conflict to a helpful conclusion, rather than letting emotion get the better of family members.

- If your child is angry, team up with them to help reduce their anger. This way, you’re separating the problem from the child.

- Later in the Learning Zone, you’ll find coping strategies for parents and carers to help them get through stressful family encounters. Look through the exercises and see what works best for you.

- By staying calm during conflict, you’re modelling this type of behaviour for your child. Even better, if you share with your child the coping strategies you use yourself, you’re showing them that they work while acting as a role model. Acting in this way is likely to teach your child how to remain calm themselves in similar situations.

Parenting and Communication

Active Listening

The key to resolving family conflict is communication.

We can’t resolve any conflict if we are not talking and listening to each other.

As a parent or carer, your role is to use the experience you’ve gathered in life to help guide your young person through life.

If teens feel that they aren’t being listened to at home, they might be less likely to confide in their family. However, if you actively listen to your young person, meaningfully taking in what they tell you and then work together to come up with solutions based on both of your needs, then you may reach a positive outcome in which both parties are satisfied.

To encourage a child or young person to talk about what’s going on for them, first, let them know that you’re listening to their concerns and that you’re taking them seriously. We call this validation.

Active listening is a set of techniques you can use to meaningfully listen. It is a highly useful conflict resolution tool that helps diffuse tension and helps resolve conflict.

_(1200_x_1820_px)_(1200_x_1850_px)_(1200_x_1900_px).png)

Making Positive Requests

A parent or a carer asking a young person to do a chore around the house is a common, if avoidable, flashpoint.

The parent or carer might think chores teach Young People responsibility and independence – or he or she is busy and needs help completing tasks around the house.

The young person might think it’s boring, it’s not as important as what they’re doing now, and they’ll get to it later.

Both sides think they are right.

Parents and carers often become tetchy when their requests are ignored as they must ask again and again, making them feel like a nag – which no one enjoys.

We can, however, get in the habit of asking for things in a way that can make a young person tune out.

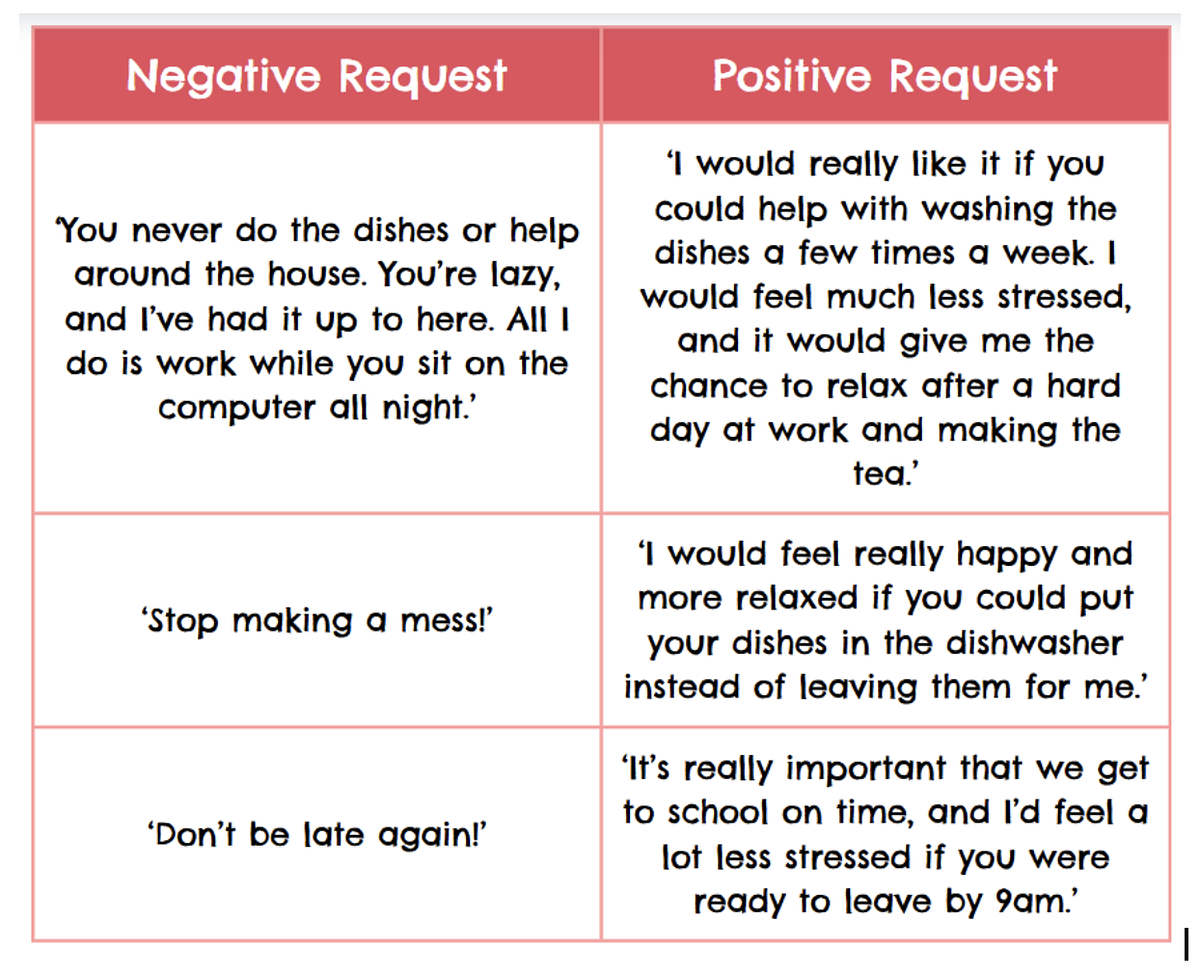

The answer is positive requests.

Positive requests give parents and carers a blueprint for asking for something in a polite yet assertive way, avoiding the sort of blaming language that can harm relationships. It helps us explain to Young People why we are asking them to do something, which should make it likelier that they will do what a parent or carer has asked them to do.

Here’s what to do.

_(1).png)

For example, you could say

1. I would really appreciate it if you (did X).

2. I think I would feel more (add feeling).

To give an example:

‘I would really appreciate it if in the future, you could tell me where you are going and when you will be back. Instead of feeling jumpy and anxious, I think I would feel much calmer, knowing that you were safe.’

Other examples of Positive Requests include:

Editing Language

Frequent conflict with your children can have an impact on mood and make parents and carers feel a bit negative. They might end up focusing on the negatives and forgetting about the positives. The short piece of audio below suggests alternatives that should reduce conflict:

- focus on the positive

- edit out complaints

- edit self-criticism

Praising and Rewarding Good Behaviour

_(1200_x_2800_px).png)

Specific Parenting Strategies

Resolving conflicts with children and teens: parenting strategies

Raising a teen isn’t an easy job. Academic pressure, social media, changing bodies – life as a teen is full of stress, and it can spill over into conflicts with family members. Adding to the pressure, teenagers are biologically programmed to separate themselves from their parents and develop bonds with people of their own age. This leads to boundaries being tested, another source of arguments within the home. Perhaps your young person ignores you when you ask them to ring off and join the family for dinner; or they’re spending so much time with friends their grades are slipping.

The following strategies have been developed to help parents who might need to think about re-setting boundaries with their young people.

Setting Boundaries Together

As teens’ brains develop, you might see normal boundary-testing behaviour increase. Brain changes in adolescence mean teenagers test boundaries as they cross back and forth over the line between childhood co-dependence, and adult independence, a line that only gets blurrier as they get older. As a parent, it’s natural to want to keep up boundaries to make sure your child is safe.

The point at which young people want to test boundaries and parents and carers want to keep them safe is where families often come into conflict.

When that happens, the following tips might come in useful.

henlo

Listen to the following example of a parent and young person not getting on - and what they did about it.

Parent Club has further advice on how parents and carers can build better relations with their pre-teens and teens, which you can access here.

Behaviour Contracts

A behaviour contract between parents and carers and their young people is a written or verbal agreement that sets clear expectations, responsibilities, and consequences for both sides to reduce the number of flashpoints and get family members speaking to each other in a way that improves rather than worsens relationships.

.png)

Family Meetings

A family meeting is a discussion which many parents find to be a helpful way to end conflict. The aim of these meetings is to give everyone in the family a chance to talk about how they’re feeling, including issues related to conflict, and for the family to work together to come up with solutions.

The short film below outlines what makes for a successful family meeting.

Managing Challenging Behaviour

If you’re dealing with challenging behaviour, including aggression, lack of engagement, or persistent refusal to adhere to boundaries, you’re not alone! The following are a few tips for managing this kind of behaviour.

Remember the Positive Things

Try to remember the positive things about your relationship with your young person, even when the situation feels hopeless.

Avoid Criticisms

Avoid criticisms as much as you can. When you do have to point out something, remember to phrase the statement so that it is the behaviour not the person that is understood to be causing a problem.

Try to stay calm

Try to stay as calm as you can (we know this is not always easy), because it sets a good role model for the young person, and they’ll find it easier to stay calm if the other party in the conflict is also calm. In general, approaching a situation with hostility will generate more hostility. If you find yourself becoming overwhelmed by emotions, and if it’s safe to do so, take a breather, a walk, before coming back to the argument when you’ve both managed to regulate your emotions.

Support your young person

Support your young person to find ways that they can use to calm down. They can try breathing exercises or relaxing activities like drawing, reading, listening to music or going out for a walk.

Set clear boundaries

Set clear boundaries with consequences consistently. If you agreed that there would be a specific consequence triggered when your young person doesn’t follow family rules and you then don’t follow through, young people will learn that there will be no consequences for not obeying rules. Consequences should be logical and never punitive or excessive. For example, if a young person is asked to turn the TV down and refuses, the TV can be turned off.

Talk to your child

Talk to your child about how they are feeling and help them recognise and name their emotions. Try to talk to them about what’s going on for them. You could use psychoeducational resources like the emotional iceberg worksheet to explore what’s going on under the surface, or the window of tolerance to talk about the different factors affecting our emotions and behaviour (more on both the iceberg and the window can be found in the Teenage Brain and Development section).

Summary

- Screentime can often be a source of conflict. How children use devices is often more important than how much time is spent with devices. Ask your children how they want to invest the time they have online and make sure it’s not wasted.

- Before attempting to resolve a conflict, take time to think about what you need and what you are feeling. The Emotion Iceberg, the Feelings Wheel and I-Statements can be useful helping us recognise and express emotions.

- Emotional regulation is important because our emotions drive how we behave and feel. If we can soothe feelings of anger, we can learn to approach conflict with calm. It’s especially important for parents because it directly affects their ability to respond to their children in a calm and supportive way.

- The key to resolving family conflict is communication. We can’t resolve any conflict if we are not talking and listening to each other. Use Active Listening to hear what your young person is telling you.

- When it comes to talking to your young person, making positive requests, editing language and giving praise are helpful.

- Families can resolve their conflicts but they have to do it together. Top-down orders from parents to young people will not be as effective or as long lasting as family contracts or regular family meetings where all sides air what’s on their mind.

Building a good relationship with your teenager | Further information from Parent Club.

_(1).png)

_(1).png)

_(1).png)