Wellbeing and Coping for Parents and Carers

Coping strategies are important. Parents and carers can help their young people deal with the physical changes they're undergoing and stress caused by social situations by teaching them coping skills. Coping skills are important for parents and carers too; you can't help your young people if you're too wrung out to be effective.

Wellbeing and Coping for Parents

After completing this section, you will be able to: understand what coping skills are and try them out; how mindfulness can reduce conflict; and how to challenge negative thoughts.

- Quick Introduction to Coping Skills

- Sitting with Emotions

- Unhelpful Thinking Styles

Quick Introduction to Coping Skills

Problem Solving

Sometimes we might need to tackle the problem head on. How we solve a problem depends on the problem itself. Here are some useful tips to get started.

Time Management

Managing our time better can help us solve problems. Here are some tips for managing our time:

- Set clear goals – you might want to start by making a list of what you want to achieve, or tasks that need to be completed. Try using SMART goals. These are S: Specific. What exactly do you want to achieve, who is involved and what are the steps to achieving it? M: Measurable. How will you know the task is completed? How are you going to track your progress? A: Achievable. Is this goal realistic? It’s good to be ambitions but we also don’t want to set ourselves up to fail. R: Relevant. Why are you setting this goal? Who is it for or what is it helping with? T: Time-bound. Give yourself a deadline to check-in with progress and complete the goal by. This helps you stay focused and stops you spending too much time on an unachievable goal.

- Prioritise tasks – think about what things are most important, and what things need to be done most urgently. Try using a Priorities Graph to sort out which tasks need to be done first. Download Priorities Graph Worksheet

- Make a timetable – when you are making a timetable it’s important to include breaks. It might be helpful to use a colour code to separate urgent tasks, deadlines, other tasks, breaks, and social activities. Timetables also help you keep track of how long a task is taking you.

Saying No

Sometimes when we find ourselves in a difficult situation, the best way to deal with the problem is to remove ourselves. It might be that we are in an unhealthy relationship that needs to come to an end, or we have been asked to do something that doesn’t feel right.

Learning when to say no is a really important skill. When something is causing us harm, mentally, physically or emotionally, it is time to say no. It’s important to recognise our own boundaries and practice setting clear boundaries with others. Saying no can be difficult, but we can do it in a way that makes our needs clear whilst still considering the other persons feelings. This is called assertive communication and we will look at this more in the relationships topic.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is coming up with ideas to solve a problem. You can do this in a group or by yourself. Sometimes it can be helpful to talk through a problem out loud and discuss different problem solving options. Here are some ideas for brainstorming

- Word Association. Shout out, or write down the first word that comes into your head when you think of the problem topic.

- 5 Whys: For a particular problem, ask the question why over and over until it can no longer be answered. For example, why is my teacher annoyed? Because I failed my exam. Why did I fail my exam? Because I didn’t have time to study. Why didn’t I have time to study? Because I forgot I had to help my mum at the weekend. Why did I forget? Because I didn’t write it down. Solution: In future I will make a revision timetable that includes my family commitments so I know how much time I have.

- Mindmapping. Write the problem in the middle of a bit of paper. Write down any related topics, ideas, thoughts and feelings. Then draw lines between the ones that are connected in some way. Start to explore the problem and see if you can write down some possible solutions.

- Starbursting. Draw a 6-point star in the middle of the page and write the problem in the middle. Each point of the star represents a question: Who, what, when, where, why, how. Work through each question to explore the problem and then possible solutions. For example, who was involved in the fight? And then who needs to be involved in resolving the fight?

Asking for Help

Sometimes we need help to solve a problem. Think about what kind of help you need and where you might get it. Can you discuss it with a friend? Is there a trusted adult you can talk to? Is there a service in the community that you can go to? If you’re not sure what help you need can you find out more information? Try mapping out what support is available to you.

Problem Solving Worksheet

Many young people might be quite independent in some ways. However, we know that the front part of their brain, the part that controls logical thinking and problem-solving, is not yet fully developed. This means that they might struggle to logically solve problems that they face.

Encouraging young people to talk about the challenges in their lives with a parent or trusted adult is a great step to take. Working together to help young people solve problems in their lives, be it big or small, is a great way of helping them develop key skills that will help them later in life.

Take a look at the following worksheet for a psychologically-based step-by-step guide to problem-solving for young people. This might be a useful worksheet to use alongside your child.

Download our Problem Solving Worksheet

Listen to Jo, a mother of teens, discuss what coping skills work for her.

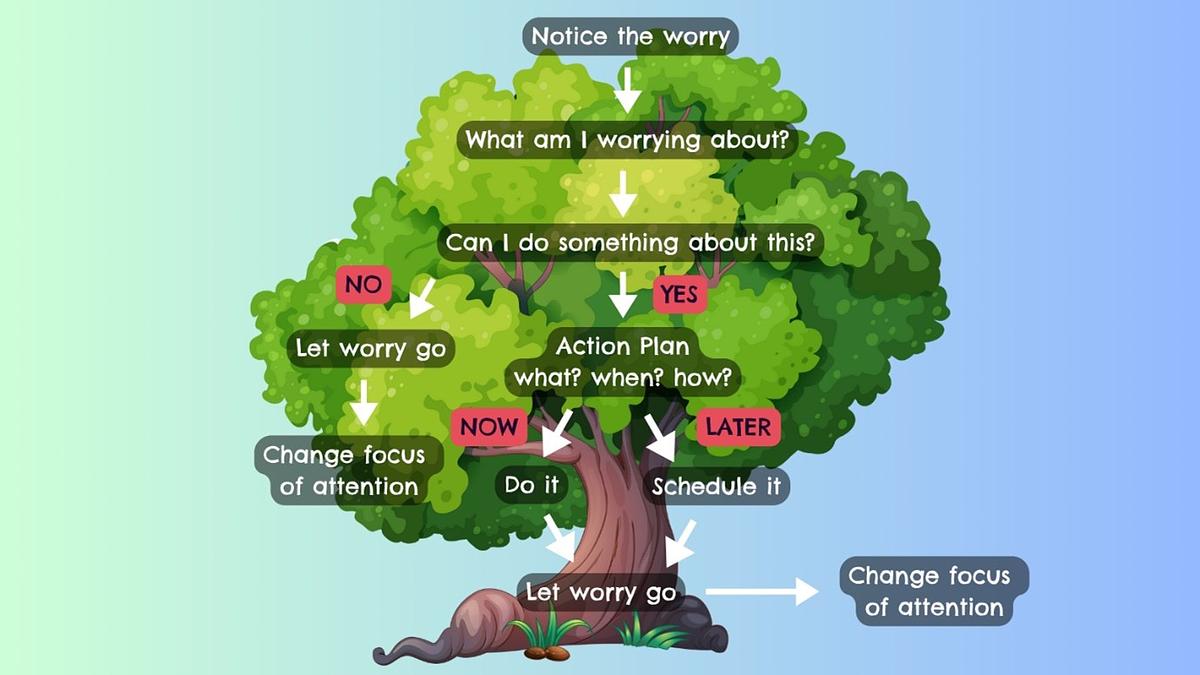

The Worry Tree

When we’re worried, we tend to let individual concerns merge until we can’t see what to do next.

‘A worry tree’ is a way to break down worries, creating a step-by-step path we can use to work out how to deal with each problem.

A worry tree is useful for any worry a young person might be facing but could be particularly useful in family conflicts, where misunderstandings, stress, and old arguments that have never been resolved can cause conflict.

A worry tree typically follows a structured approach:

- Identifying the Worry – The peak of the tree begins by asking you, first, to notice the feeling of worry and then describe it.

- Deciding If It’s Controllable – The first ‘branch’ splits into two categories: worries that can be addressed and those that cannot. We can address concrete worries like struggling with maths homework or a misunderstanding between friends. Other worries might be too big for us to solve like distressing world events.

- Taking Action or Letting Go

- If the worry is controllable, the tree branches into possible solutions, leading to an action plan.

- If the worry is uncontrollable, the tree guides individuals toward coping strategies such as mindfulness, reframing thoughts, or seeking help.

By bringing worry trees into family discussions, families can break down their worries, and try to solve problems or let the worry go.

Sleep Strategies

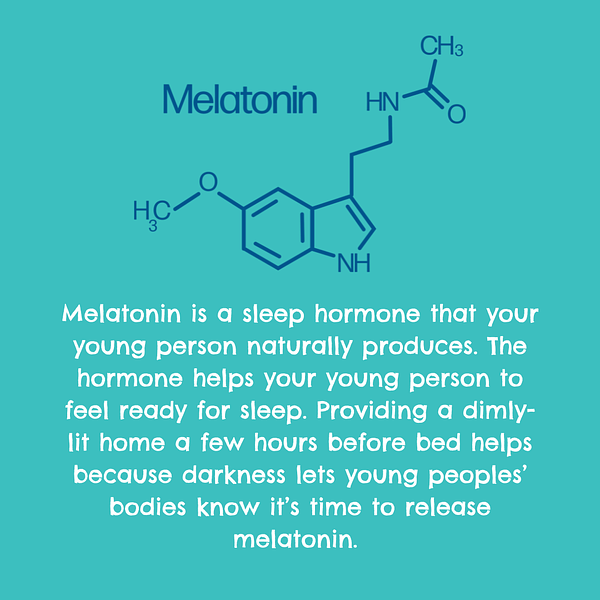

Many teenagers struggle with sleep (for more information on the teenage brain and sleep, head to the section titled ‘Teenage Brain Development’), and a lot of parents look for ways to help their young people get a good night’s sleep.

Lack of sleep could heighten emotions and reduce patience, which could make disagreements more intense, or worsen family conflict . Well-rested family members are better able to communicate calmly, listen actively, and problem-solve effectively.

The Stress Bucket

If you’re stressed and are unsure why it’s got to the level it has and what you can do about it, the stress bucket could help.

The stress bucket can help family members visualise their stress levels and to see how different causes of stress are adding to an emotional overload.

For families, the stress bucket helps people visualize their stress levels and understand how different factors contribute to emotional overload. The stress bucket is useful for naming the things that trigger us emotionally, improving control of emotions, and fostering healthier communication.

How the stress bucket works

- The Bucket – Represents a person’s capacity to handle stress. Each person has a different-sized bucket, depending on factors like personality, past experiences, and coping skills.

- What Causes Stress (Water Inflow) – Stress comes in many forms including work, financial pressures, unresolved family issues, and personal anxieties. They help fill the bucket.

- Coping Mechanisms (Drainage System) – Healthy coping strategies, like exercise, talking to loved ones, or practicing mindfulness, act as outlets that help drain stress from the bucket. Without these outlets, the bucket overflows, leading to emotional outbursts, anxiety, or conflict.

By visualizing stress in this way, families can work together to support each other, develop healthier coping mechanisms, all which could contribute to the creation of a more harmonious home life.

Create your own stress bucket or use the illustration in the downloadable Stress Bucket PDF

How Mindfulness Can Help Resolve Family Conflicts

Emotions as Messages

Emotions carry information to the brain. We can think of them like messages; they are trying to tell us something. Often, they are making us aware of a need that is not being met. Emotions make us aware of what is important to us in a situation and therefore help guide our actions and decision-making.

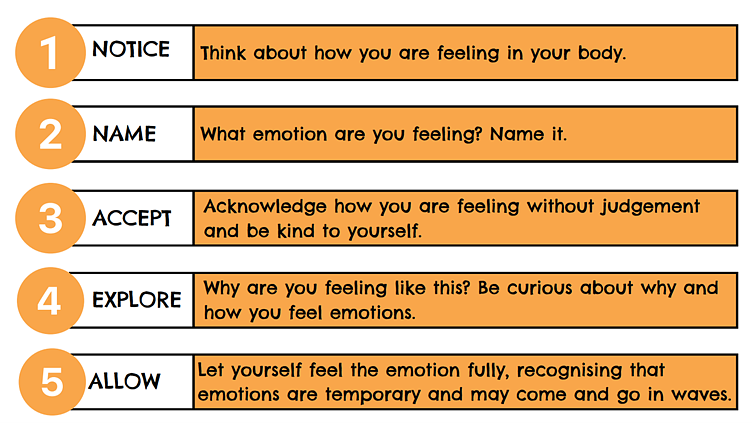

Sitting with Emotions

Sometimes it is not possible for us to change the way we are feeling, and it can be unhelpful to ignore or dismiss our emotions. Instead, we might need time to process how and why we are feeling a certain way and accept our emotions. We might need to ‘sit with’ our emotions before we are able to express them to others. If we dismiss our emotions, they might come out in less healthy ways.

Sitting with our emotions helps us take a curious, non-judgemental stance about our emotions. We are the ‘watcher’ of our emotions rather than getting swept up in them. This level distance from our emotions helps prevent us from becoming overwhelmed by them, and allows us to simply experience them, process them, and ride the emotional wave, until it passes.

Try these steps to process and accept your emotions:

Sitting with Emotions and Mindfulness

Sitting with emotions is a practice of allowing ourselves to acknowledge our feelings without judgment or avoidance. It’s an essential aspect of mindfulness, which emphasizes being present in the moment. When emotions such as sadness, anger, or anxiety arise, the instinct is often to suppress them or to distract ourselves. However, these approaches can lead to unresolved feelings.

Mindfulness encourages us to pause, breathe, and observe our emotions as they are – temporary experiences rather than fixed identities.

By sitting with emotions, we give ourselves space to explore their origins and understand the needs or unmet desires they might represent. This doesn’t mean we indulge in them but rather notice them with compassion and understanding.

Managing Our Emotions: Mindfulness

Practicing mindfulness, either yourself or your young person or both, during periods of emotional difficulty encourages self-awareness and resilience.

Techniques such as mindful breathing, body scans, or labelling emotions (‘I notice sadness’) can create a sense of distance from whatever is troubling us, which can make it easier to respond thoughtfully rather than react impulsively.

Ultimately, sitting with emotions can build emotional intelligence and helps us navigate life’s challenges with greater clarity and self-compassion, which can help transform discomfort into opportunities for growth and deeper self-understanding.

Below you will find a link to more information about mindfulness techniques and a recording of a guided mediation as a first step into trying mindfulness.

What is Mindfulness?

Do you ever find yourself doing repetitive, everyday tasks, and going into autopilot? You may be daydreaming or worrying when you do this. Mindfulness is the opposite of this; it means pulling all your focus onto the here and now, in other words, paying attention to what’s happening and being fully present in the moment. You might have tried mindfulness before, and you may have struggled with it. That’s okay! It’s perfectly natural for us to go into auto-pilot mode when carrying out repetitive tasks. Mindfulness has myriad benefits on our mental health though, and the more we practice it, the more natural it becomes. It’s useful to think of it like any other skill: through time, patience, and practice, it will develop.

Why Try Mindfulness?

When you stop to notice what is happening around you, you begin to focus on your senses. This can help you, and your children, to return to a calm state when overwhelmed, angry, upset, or experiencing other uncomfortable emotions. Studies show that practicing mindfulness has been linked to lower levels of parental stress, improved parenting strategies and better parenting skills. It has also been found to improve children and adolescents’ emotional regulation skills. Examples of mindfulness exercises include:

_NEW_(1000_x_2400_px)_(1000_x_3600_px)_(1000_x_3800_px)_(1000_x_4000_px)_(1000_x_4200_px)_(1).png)

This short guided meditation is designed to help parents and carers find a moment of calm when emotions run high. If you’re feeling overwhelmed or agitated during or after a family argument, this gentle audio will help you reset, breathe deeply, and return to the situation with a clearer, calmer mind. It’s a practical pause — a tool to support emotional regulation when you need it most.

Find a quiet space if possible, sit comfortably, and press play. You can return to this meditation whenever you need help calming down or creating space to respond rather than react.

Unhelpful Thinking Styles

Unhelpful thinking styles are patterns of negative or irrational thinking that can distort reality and lead to stress, anxiety, or conflict.

Types of unhelpful thinking styles

Sometimes it is the way that we’re thinking about a situation that is causing the problem and resulting in uncomfortable emotions and having an impact on our behaviour. After we learn to recognise unhelpful thinking styles we can then challenge and reframe these thoughts.

Fortune telling

We can’t predict the future, not that that stops people trying. It’s fine and natural to try to guess what the consequences of our actions will be, but there’s a problem if we predict everything we try will go wrong. It can stop us from trying anything! Signs fortune telling has gone wrong are finding yourself saying things like,‘If I ask my son to help out round the house, he’s going to hate me.’

Black and White Thinking

Thinking in extremes isn’t helpful. We can think this way about ourselves, believing that if we’re not perfect we’re no good. We might consider other people or situations in a similar way, thinking someone can only be good or bad, ignoring all the shades of grey in between. For example: ‘If I don’t get this job, I’m a complete failure.’

Mind Reading

This is another one where we might think as if we have a supernatural ability. The reality is, you don’t know what other people are thinking. A lot of the time, others will be thinking differently from how we might expect. Examples: ‘My daughter must think I’m stupid.’

Catastrophising

This thinking style leads us to worrying about the worst possible scenario coming true, and assuming we won’t be able to cope. Most of the time though, it doesn’t go as badly as we might think, and even if it did, we’d manage to cope. Thoughts might include: ‘My son hasn’t come home and it’s midnight, he must be in trouble.’

Feelings as facts

This is when we believe that if we feel something, it must be true. For example, ‘I feel anxious about my son going to a party, which must mean there’s something dodgy about it, so I won’t let him go.’

Labelling

We might talk about ourselves in damaging ways without thinking about it. We might talk to ourselves in ways we would never dream of addressing a friend! This kind of negative thinking is unhelpful and unfair to ourselves. For example, ‘I made a mistake at work; I'm such an idiot.’

Over-estimating danger

This is when we worry about something so much we end up tricking ourselves something terrible will happen, even if it’s unlikely to actually happen. For example, ‘My daughter is going to a festival with people I don’t know, she’s going to take drugs and end up in danger. I won’t let her go.’

Filtering

We might pay more attention to the bad things that happen, ignoring all the positives. Being biased towards the negative can stop us seeing the full picture accurately. For example, ‘My son looked at me contemptuously when I asked him to wash the dishes, I must have messed up’, while ignoring that he did in fact go on to wash the dishes without complaining, and did a good job too.

‘Should’ statements

Thinking ‘I should…’ or ‘I must do [X]’ puts pressure on ourselves. Examples: ‘I should have been stricter with my son.’

Thought Challenging

Negative thoughts that don’t go away or unhelpful patterns of behaviour are likely to cause our mood to suffer over time. In turn, this might have an impact on our behaviour. It could lead us to withdrawing, spending less time doing the things we enjoy, or finding ourselves in conflict with others more frequently.

Thought challenging involves finding ways to think differently or asking yourself questions which challenge the thoughts. Questions such as:

_(1).png)

Summary

- The front part of the teenage brain, the part that controls logical thinking and problem-solving, is not yet fully developed. This means that teenagers might struggle to logically solve problems that they face.

- Working together to help young people solve problems in their lives, be it big or small, is a great way of helping them develop key skills that will help them later in life.

- Emotions carry information to the brain. We can think of them like messages; they are trying to tell us something Often, they are making us aware of a need that is not being met.

- Sometimes it is not possible for us to change the way we are feeling, and it can be unhelpful to ignore or dismiss our emotions. Instead, we might need time to process how and why we are feeling a certain way and accept our emotions. We might need to ‘sit with’ our emotions before we are able to express them to others.

- Practicing mindfulness, either yourself or your young person or both, during periods of emotional difficulty encourages self-awareness and resilience.

- Unhelpful thinking styles are patterns of negative or irrational thinking that can distort reality and lead to stress, anxiety, or conflict.

- Thought challenging involves finding ways to think differently or asking yourself questions which challenge the thoughts.